This year we have been inundated by so many things happening from all directions, it’s hard to choose what to focus on. For the sake of this end of the year blog, we’re choosing to discuss two of the most pressing issues we see as inextricably linked: climate change and gender equity. As we leave 2021 and all the challenges it has brought us, one key truth continues to arise: if we devalue women—women’s labor, women’s bodies, women’s minds, and women’s choices—with outdated norms, policies, and practices, we will never realize widespread global equity or peace. Gender ties into almost every major issue, including (if not especially) climate change. There are three key ways in which this is true:

- Climate change affects women more deeply and on a wider scale

- The issue of reproductive rights is—and always has been—a matter of human rights

- Reproductive justice is key to bringing about global gender equity

Systems change is the primary answer to these woes—more so than any individual consumer could ever hope to alter or achieve in a lifetime, and here’s why: the majority of global warming and economic inequity is caused by an elite few. These elite few, in turn, are complicit in a process that places a heavy burden on primarily lower-income women and women of color, by profiting from the invisible labor of the care economy and creating tangential narratives that distract the masses from the truth.

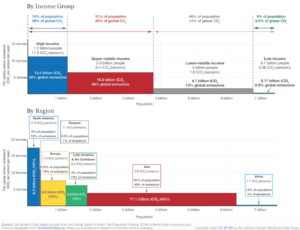

For instance, the environmental movement has traditionally been guided by myths and miseducation around who is responsible for climate issues. These myths are racist and misogynistic at worst, and misleading at best. There are two prominent myths that are especially damaging: 1) individuals are responsible for most environmental degradation; and 2) population growth is the devastating reality climate activism should primarily focus on. In fact, 100 of the world’s top companies produce over 70% of global emissions, and the global fertility rate actually fell from 3.2 births per woman to 2.5 from 1990 to 2019. These myths do nothing to help progress us toward goals of conservation or climate action. Instead, they produce fear of scarce resources that diverts public attention away from the main culprits and incorrectly blames poor women (mostly women of color) for having too many children. Research from Our World in Data shows how the richest half of the world emits 86% of global carbon dioxide emissions, despite having the lowest fertility rates.

“The richest half of the world emits 86% of global carbon dioxide emissions, despite having the lowest fertility rates.”

The harm around these myths embodies a practice of blaming already vulnerable communities—people who are more deeply impacted by the effects of climate change—when in fact they are least culpable. For example, the United States accounts for less than 5% of the world population and yet is responsible for 15% of total emissions. Meanwhile, countries in sub-Saharan Africa are commonly cited as areas of problematic population growth and are among the lowest carbon polluting. Women in these areas are also more likely to suffer from a dependence on agriculture and the informal economy for their families—two of the most vulnerable forms of labor for lower-income communities.

Women in particular are left with little means of supporting or protecting their families during periods of climate disasters such as flooding or droughts—when men are often forced to seek work outside of their communities. State regulations governing banking and land ownership are also rooted in gender discrimination. Only 15% of land around the world is owned by women, and because male family members hold the title for land ownership, banks tend to deny women loans.

Aligning—or misaligning—with these myth narratives is rooted in racist, biased beliefs that poor people are responsible for the climate situation. The reality is, the problem isn’t really numbers; it’s the unequal distribution of existing resources and basic necessities to the majority of people on the planet. We have enough resources to feed everyone on the planet; however, we can’t currently sustain 7.5 billion people while the richest 10% of the population continues to exploit poor communities and the natural world. We could certainly support most if not all people if the wealthiest percentiles had a smaller (and fairer) share. A social justice approach to climate action necessitates broad systemic change by holding governments and businesses accountable for reducing their reliance on fossil fuels and mitigating the disproportionate impact felt globally by people with the fewest resources.

Abortion absolutely ties into this discussion, as the right to abortion is a women’s right to her own body and so her own life. Tiffany Cabán, New York City councilwoman said it best: “The core of the fight for reproductive justice is the same as all of our liberation struggles. It is about freedom from control, coercion, and exploitation—namely of the most vulnerable and marginalized communities. If banning abortions were about genuine care for human life, then the same people trying to take away our reproductive rights would also be fighting just as hard to give people the resources to parent.”

Women and Climate: The Real Story

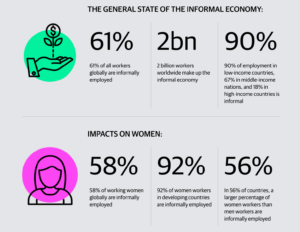

Women tend to struggle more economically than men, a condition that has only worsened during the pandemic. In 2020, women made up 39% of global employment and accounted for 54% of overall job losses. The gendered nature of work explains the disproportionate impacts on women, as women are both over-represented in many of the most affected sectors (e.g. low-wage service jobs), and are responsible for the majority of unpaid care work including childcare, caring for the elderly, cooking, and cleaning. With the rise of COVID-19, women experienced an increase in these responsibilities, subsequently causing them to drop out of the workforce at a higher rate than men. These numbers are exacerbating already existing vulnerabilities within the informal economy (see the infographic below for more detail).

In a nutshell, according to feminist climate researcher, Bernadette P. Resurrección: “the drivers of climate change, environmental degradation, and gender and social inequality are not separate but interconnected…[and] draw from the combined extraction of nature and the exploitation of cheap labor from poor women, colonized and racialized groups.” Women work two-thirds of the world’s working hours, produce half the world’s food, and earn 10% of the world’s income. Women are, in short, responsible for keeping the care economy running, and yet rarely if ever benefit from or are compensated for it.

“Women work two-thirds of the world’s working hours, produce half the world’s food, and earn 10% of the world’s income.”

The focus on markets and economy as a solution is also problematic in how it consistently overlooks unpaid labor—the labor of women—as an essential function of our world. Capitalism has allowed the majority of us to ignore other forms of value that don’t instantly or obviously produce a tangible, market-based product. I wonder, could you quantify everything you care about? Love? Probably not (nor should you try). Despite ignoring the care economy, it is precisely what allows the market to exist and even flourish. Capitalism in its current state exploits natural resources and the unpaid labor—especially women of color—to further immediate gains for a few selfish people in spite of long-term losses for the masses and the overall erosion of collective values.

According to a recent report from Women Deliver, the impacts of climate change have demonstrated detrimental effects on women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR). This includes: negative impacts on maternal health; unstable conditions that result in increases in gender-based violence (e.g. harmful practices such as child marriage and domestic violence); and strained health systems during climate-related disasters that further hinder access to SRHR services, to name the top three. The thread that connects gender and climate can be understood as the meeting of vulnerability in social class and identity, and the common qualifiers that apply to each (e.g. gendered, racialized, and colonized).

The crux of the matter is, the living conditions for many women in communities around the globe are subpar, full of occupational hazards, inaccessible resources and rights, an unreasonable list of care obligations, and poor housing options—all of which put them at greater risk to climate change and natural disasters. In short, without the social well-being and protection of women being integrated into climate action, there can be no authentic climate justice. Power as it is currently understood and practiced is being used to subjugate and marginalize through traditional definitions of authority and knowledge—even (if not especially) in our philanthropic response to global issues. To read more about the impacts of climate on women, see the table below.

We are only just beginning to realize the magnitude of a changing climate’s effect on our physical and mental health as the disruptions to our lives and those close to us have been deep and lingering. COVID-19 can be understood as “a crisis of environment and development…that has brought to our stark awareness that our economies and lives are founded on care: usually on the back of women’s unpaid and underpaid care work, on the shoulders of essential workers who are responsible for ensuring food security, collecting our waste and recyclables, but whose work and labor are widely undervalued and exploited… Nature and women’s labour are both treated as infinitely elastic and readily exploitable, jointly undervalued, subsidizing all economies.” (Resurrección, B.P.)

We are only just beginning to realize the magnitude of a changing climate’s effect on our physical and mental health as the disruptions to our lives and those close to us have been deep and lingering. COVID-19 can be understood as “a crisis of environment and development…that has brought to our stark awareness that our economies and lives are founded on care: usually on the back of women’s unpaid and underpaid care work, on the shoulders of essential workers who are responsible for ensuring food security, collecting our waste and recyclables, but whose work and labor are widely undervalued and exploited… Nature and women’s labour are both treated as infinitely elastic and readily exploitable, jointly undervalued, subsidizing all economies.” (Resurrección, B.P.)

“Nature and women’s labour are both treated as infinitely elastic and readily exploitable, jointly undervalued, subsidizing all economies.”

A Feminist Path Forward

What can we do to change the climate narrative so that the most vulnerable members of society—those suffering socio-cultural discrimination—do not continue to suffer the worst consequences of climate change? There is evidence to support integrating climate adaptation efforts with gender equity by improving health systems with girls education and women’s economic empowerment. More resilient health systems and better SRHR, especially in the aftermath of natural disasters, can reduce the impacts of climate change on vulnerable communities. In a similar vein, increasing girls’ and women’s resilience and adaptive capacity in dealing with climate change (especially regarding leadership and decision-making) can ensure the impacts of climate change are lessened and properly addressed. Adaptation needs to include SRHR because without addressing these issues, vulnerable populations’ adaptive capacity will be drastically reduced.

Feminist research on gender and climate suggests building deliberative forms of democracy to debate sustainability goals and values in truly inclusive and feminist ways, so the change that is brought about is authentically beneficial for all and doesn’t just serve the upper echelon that seeks to stimulate markets for personal gain. Ecofeminism offers an alternative to our current structure as a production exercise in initiating and harnessing transformative and innovative programs and responses that utilize a feminist praxis and ethics of care.

Parijat Academy’s grassroots menstrual health program brings resources to underserved, rural areas

“A feminist ethics of care therefore recognizes, sustains, and unifies the symbiotic and interdependent relationship between nature and society. It is this rationale of care for humans and nature that produces, reproduces, and sustains life and livelihoods and gives preference to provision, need satisfaction and enforcement of rights over the principle of efficiency and the egoistic utility maximization enshrined in the careless and reckless accumulation economy.” (Resurrección, B.P.)

On a systems level, this also means we get serious about funding grassroots-led organizations and social movement collectives that have been working to address key global issues for years—and who desperately need support. Leading donor organizations that tout the power of partnerships could also follow through on their word and invest in building authentic solidarity and shared interest with their grantees.

As we enter a new year, the world is now eight years until 2030—the year we will supposedly achieve the 17 Sustainable Development Goals outlined by the UN. And yet, some estimates have suggested it would take until 2094 to achieve these goals if we progress at our current rate. While there are many underlying causes of why this is the case, it is in a large part due to a lack of commitment to funding systems change—especially in terms of how the philanthropic sector as a whole approaches grant making—and all the outdated funding practices this entails.

The overall lack of flexibility to funding primarily serves to overwork exhausted community engagement workers and diminish innovative initiatives before they can ever flourish. For far too long, community organizations have requested a more relational, trustworthy approach to philanthropic giving—one that invests in iteration and learning and takes a broader view of monitoring and evaluation, to reflect the complexity and uniqueness of issue areas.

“Indigenous groups and women in particular need to be recognized as valuable pieces to solving the complex puzzle of climate change.”

Hand in hand with this is also creating space for the voices of people who are experiencing the brunt of climate change—and doing so in a dignified, ethical way. Without this critical storytelling piece, the narrative will always be skewed. The same goes for decision making. Indigenous groups and women in particular need to be recognized as valuable pieces to solving the complex puzzle of climate change. They are and always have been at the center of it all.

Aimoni Tumung, co-founder of Parijat Academy

By involving gender experts in environmental and climate programs, solutions will not be limited to only traditional experts with conventional knowledge. Indigenous groups have been paving the way for decades on environmental conservation and knowledge and should be as consulted and involved as mainstream environmental experts.

Care will also have to be taken in how climate adaptation programs treat vulnerable communities so further harm isn’t done to them—especially to women—meaning communities will need to be consulted on what solutions would work best for them. To read more about these recommendations, see this Women Deliver report and this Heinrich Böll Foundation report.

Resources

- Ashoka, Catalyst 2030, et. al. (2020). Embracing Complexity: Towards a shared understanding of funding systems change.

- Ford Foundation, The Guardian. (2020). More than 2 billion workers make up the informal economy.

- Gaard, G. (2015). Ecofeminism and climate change. Women’s Studies International Forum.

- Heinrich Böll Foundation, Wichterich, C. (2020). The Future We Want: A Feminist Perspective (Vol 21).

- ICRW. (2020). Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) is a Climate Issue: Recommendations for U.S. Foreign Policy and Assistance.

- Ms. Magazine. (2021). Population Control Isn’t the Answer to Our Climate Crisis.

- Ms. Magazine. (2021). Women in the Global South Must Be at the Forefront of Our Climate Emergency Response.

- OXFAM. (2020). Power, Profits and the Pandemic: From corporate extraction for the few to an economy that works for all.

- Resurrección, Bernadette P. (2021). Gender, Climate Change and Disasters: Vulnerabilities, Responses, and Imagining a More Caring and Better World.

- Ritchie, H. (2016). Global inequalities in CO2 emissions. Our World in Data.

- UN Environment Programme. (2015). Climate Change and Human Rights.

- Union of Concerned Scientists. (2020). Each Country’s Share of CO2 Emissions.

- Women Deliver. (2021). The Link Between Climate Change and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights.